A brief history of polio:

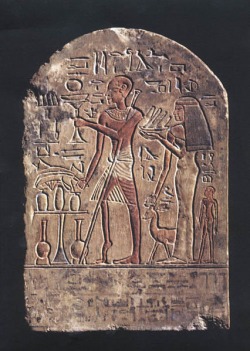

Polio has plagued mankind for centuries. An Egyptian tomb carving from 1300 BC depicts a dead priest with a foot deformity typical of paralytic poliomyelitis. This suggests that polio may have been endemic to the area for thousands of years.

Early efforts at exploring the disease began in 1789, when Dr. Michael Underwood attempted the first known clinical description of polio, titling his work "Debility of the Lower Extremities."

Dr. Jacob von Heine continued this work in 1840 by conducting the first systematic investigation of the disease, developing the theory that the disease could be contagious.

In 1894, the first significant outbreak of "infantile paralysis" was documented in the United States. This outbreak subsequently came to be known as poliomyelitis.

In 1916, New York experienced an epidemic of polio. Because of the yet unknown high rate of asymptomatic carriers, attempts at quarantining affected individuals had no effect. This heightened concerns about the disease and accelerated research into how the disease was spread.

The three serotypes of polio were identified by Sir Macfarlane Burnet and Dame Jean MacNamara in 1931.

In 1948, John Enders, Thomas Weller, and Frederick Robbins succeded in growing poliovirus in live cells. The poliovirus was the first of its family to be isolated and was the first of its kind to be grown and isolated in non-neural tissue. This accomplishment allowed for easier research into the development of a vaccine. Six years later, they earned a Nobel Prize for their accomplishment.